Have you heard of ecological exile?

The scientific expression ‘ecological exile’ is now sadly becoming a part of our common vocabularies, because it is becoming a much more common occurence. Just like the climate crisis it stems from, the phenomenon is now global.

What is ecological exile?

The term “ecological exile” refers to the forcible displacement of settled populations due to the ecology and climate crisis.

It is the academic term for being forced to leave one’s homeland because its environment is no longer safe or healthy, thanks to climate change. Thanks to abnormal rising sea levels, accelerated erosion, water shortages, agricultural overexploitation or geological changes, such as soil sinking or softening.

The designation became more widely used amongst academics after Canadian researcher Derek Galdwin, fellow of the country’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, published his book Ecological Exile: Spatial Injustice and Environmental Humanities.

From Latin America to Europe

Seasoned scientific journalist, founder and director of magazine Aquí Latinos, Mr. Perez Uberhuaga agreed to share with us his testimony on the subject.

Edwin Perez Uberhuaga emigrated to Europe 15 years ago from Bolivia. He married Esther, a lovely French woman. He now lives between Spain and Switzerland, traveling all over the continent to report on the ordinary and extraordinary lives of Latin Americans in Europe.

The magazine is a compilation of personal stories and think pieces on political events in Europe and the Americas. It reflects on the existence of latinos in Europe, some of whom did not move to this side of the pond by love, choice or ambition, but because ecological causes forced them to move.

Regarding the subject, Mr. Perez Uberhuaga wrote for us:

“I am a witness to modern ecological exile. In more than 30 years of traveling around the world as a journalist, I have witnessed a phenomenon that is not new but has intensified greatly: ecological exile. Almost everyone talks about political, economic, labor exiles, or migrations for study, work, love, or adventure, but few refer to the painful departure from a rural center affected by climate change or natural or war-induced tragedies.

I have seen farmers suffering from droughts or floods and then seen them in a European city suffering perhaps twice or triple the migration trauma, not understanding the rules of the “big city” (metro, trams, bank payments, living in apartment blocks, etc). I was in the Amazonian region of Bolivia, Peru, and Brazil (Bolpebra), affected by the overexploitation of gold and the earth for chemicals used to make cocaine. I visited the disappeared and ancient Lake Poopó in Oruro, Bolivia, walked in the hot zone of Barinas in Venezuela, or the Caribbean Sea of Colombia, whose fish do not live as long as they used to.

I looked at the now-contaminated Nile in Egypt or the more or less well-preserved waters of the Dead Sea in Israel, where the hydroponic system fights to sow in empty deserts. More recently, I saw the Tagus and Douro rivers that reach Spain and the birth of the Atlantic in Portugal, whose waters are also contaminated.

I have crossed the Swiss, French, and Italian Alps by bus, where the cold and snow forced many to go to the Latin American paradise. Today, these snowy mountains are losing snow and forcing artificial production for winter sports.

To all the garbage that existed before, now add the existence of masks, condoms, and beverage and medicine containers, which are ingested by animals that we later hunt and eat, within a very dangerous vicious circle.

Political and economic exile almost have clear rules. But ecological exile is more difficult to understand and explain.”

How does one fathom that an indigenous or farmer has to pack their bags to move to strange territory? How does one explain to a consul or a migration agent that there is no alternative?

Edwin Pérez Uberhuaga for Paradigme Mode

“In countries like Colombia, there was not only ecological exile, but also peasant leaders that were made to leave their land for opposing transnational corporations irrationally exploitating their lands’ water and natural resources.

In my three books and a hundred editions of the Aqui Latinos magazine, I try to inform about that process and, like others, show the “face of migration” that can take on many forms: field-field, field-city, or field-strange country.

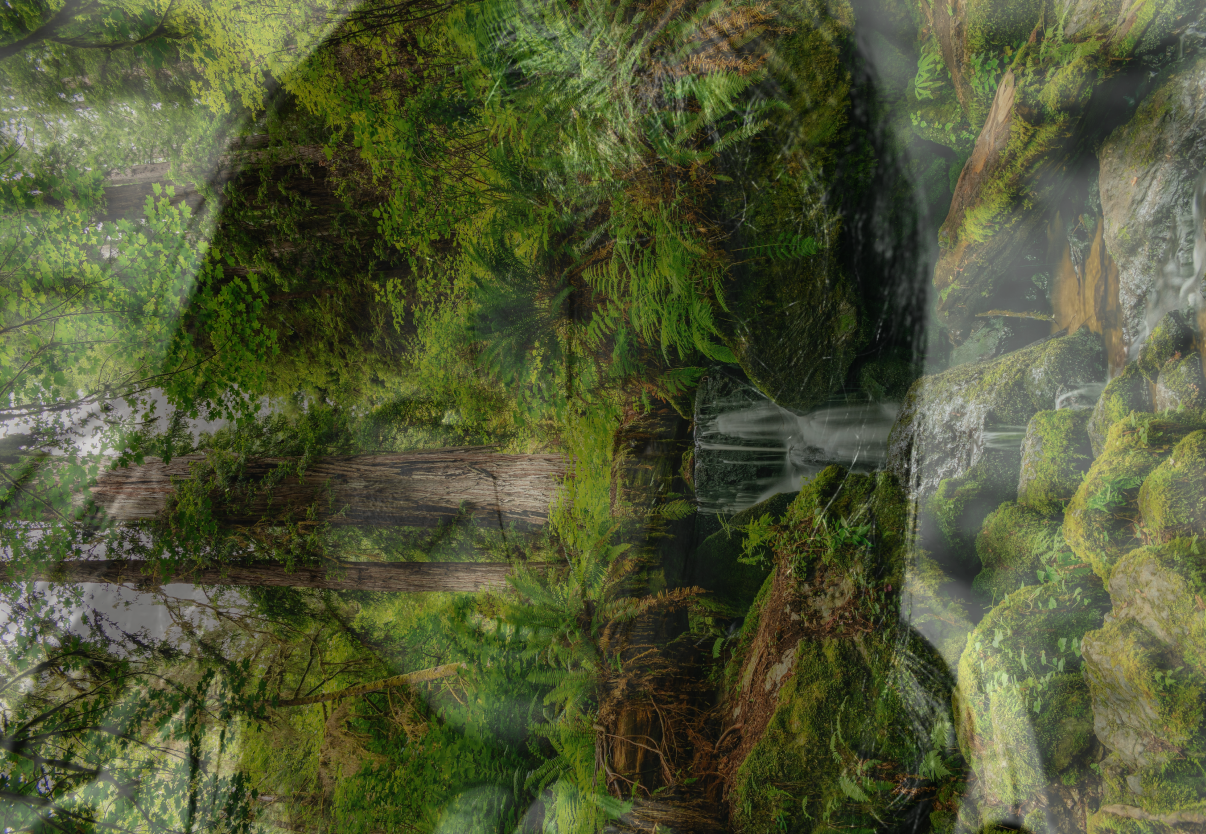

Precisely that face burned by the sun and those calloused hands that today must fulfill other trades show us that there is still a great pending issue with this type of exiles. Born and raisedwith their Pachamama (Mother Earth), they are now far from their mountains, forests, and seas, without anyone understanding the magnitude of their condition as victims of modern ecocide.

Either way, we must return their lands, sanitized and productive. We must also understand the roots of their migration. It is the least we can do to return to a balance between man and nature” said Edwin Perez Uberhuaga on February 20th, 2023.

An added tension for European leaders

While Europe already faces political and economic migratory crisis, the phenomenon continues to spread. If it first became apparent when oversea migrants started to recount their stories and reasons for emigrating, it is also well underway inside our own walls.

Ecological exile has moved — and continues to move — people from Eastern to Western Europe or from the Mediterranean to northern lands, inside and outside of the Schengen space.

In-Depth Resources

- Ecological Exile: Spatial Injustice and Environmental Humanities, D. Galdwin, 2018

- Aquí Latinos Internacional, Testimony by Edwin Perez Uberhuaga, 2023

- That sinking feeling again: From Joshimath to Shimla via McLeodganj and Dharamshala, Ashwani Sharma, 2023

- Water scarcity, SIWI — Leading Expert in Water governance